Photo by Davide Cantelli on Unsplash

Throughout the ages, God tends to be blamed for a lot of unfortunate events (it isn’t just a late 20th/early 21st Century phenomenon).

In the Scots law of delict (and in the English law of tort), there is a potential defence to an action for negligence known as damnum fatale or an act of God. The essence of this defence so the defender (or respondent) asserts is that s/he could not prevented harm from occurring to the victim because it was a completely unforeseeable event.

When discussing this defence, the standard case in Scotland to which many commentators refer is Caledonian Railway Co v Greenock Corporation (1917). In this case, the House of Lords was far from impressed by the Greenock Corporation’s argument that freakishly heavy rainfall during summer should be treated as an unforeseeable occurrence – in other words, an act of God. The Corporation had diverted the course of a local burn (stream) in order to fill a swimming pool. Heavy rainfall occurred and the water from the pool overflowed and flooded neighbouring property which belong to the Caledonian Railway. The Greenock Corporation was found liable to the Railway for the damage caused. The amount of rainfall might be unusual for other places in Scotland, but certainly not for Greenock. Knowing Greenock well, I can attest to the amount of rain that falls there on a regular basis and I think an argument could easily be made to confer upon it the dubious accolade of the wettest town in Scotland.

The defence of damnum fatale arose recently (and briefly) in a case before Lord Glennie in the Outer House of the Court of Session (see Allen Woodhouse v Lochs and Glens (Transport) Ltd [2019] CSOH 105).

I will say, of course, from the outset that Lord Glennie sensibly rejected any possible part that this defence might have to play in proceedings:

‘But I am left with this concern. My finding on the evidence is that the weather conditions were unpleasant and the wind was strong – but there was nothing exceptional about the conditions, winds of that strength were foreseeable, and extreme turbulence, being a feature of the topography of that area, could also be foreseen. For that reason I would have rejected the defence of damnum fatale, had it been necessary to consider it.’

The facts of the case were as follows:

Mr Woodhouse was a tourist, who was on a 7 day Ceilidh Spring Break, staying at the Loch Awe Hotel. As part of the package, the defenders (Lochs and Glens (Transport)) took the tourist party on day trips using one of its buses. On one of the day trips, Mr Woodhouse and his fellow tourists had stopped near the top of the well known beauty spot, the Rest and Be Thankful. The weather was particularly foul that day and, understandably, most of the tourists did not take the opportunity to leave the bus and go out to the viewpoint.

This part of the excursion was all too brief and the bus driver decided to leave the viewpoint. Shortly after the bus had pulled away, the driver became aware that the passenger door was slightly open and she stopped the bus to close it. When this was done, she started the bus and headed down the Rest and Be Thankful on the Inveraray side. By this point, the force of the wind had increased dramatically and the bus was effectively heading directly into the path of a violent gale. To cut a long story short, the driver took (what she believed were) reasonable precautions and moderated her speed and driving technique. Nevertheless, despite these measures, the bus eventually went off the road due to a combination of unfortunate events i.e. the uneven slope just above Loch Restil; the lack of a safety barrier at the time of the accident; the high winds and the build up of mud on the vehicle’s wheels as it attempted to navigate the grass verge which affected the braking system.

As a result of the bus leaving the road, Mr Woodhouse suffered injuries and he brought an action for compensation (£15,000) against Lochs and Glens (Transport) for the alleged negligence of its employee. Although Mr Woodhouse’s claim was initially lodged in the Sheriff Court, it was later transferred to the Court of Session in recognition of the importance of some of the issues and consequences which it raised (there were 51 other passengers on the bus that day).

Due to the fact that control of the situation was the responsibility of the defenders and its driver, the burden of proof switched to the defenders to demonstrate that they were not liable in negligence to Mr Woodhouse. The merits of his claim would, therefore, stand or fall on the basis of Mr Woodhouse’s reliance on the legal principle known as the facts speak for themselves (res ipsa loquitur).

In dismissing Mr Woodhouse’s claim for damages, Lord Glennie noted that:

‘I am persuaded on the evidence that the defenders have discharged the burden on them of proving that the accident happened without their negligence. The evidence that the coach was well maintained and did not suffer from any relevant pre-existing defect was not challenged; indeed it was a matter of agreement in the Joint Minute lodged in process by the parties. The only challenge, the only suggestion of fault advanced by the pursuer, was in relation to the actions of the driver.’

Critically, his Lordship went on to say that, although the bus driver may have misjudged the actual speed at which she was driving the vehicle, she had not been driving dangerously.

Taken together, all of these factors demonstrated that neither the defenders nor the driver were liable in negligence to Mr Woodhouse.

A link to Lord Glennie’s Opinion can be found below:

Postscript

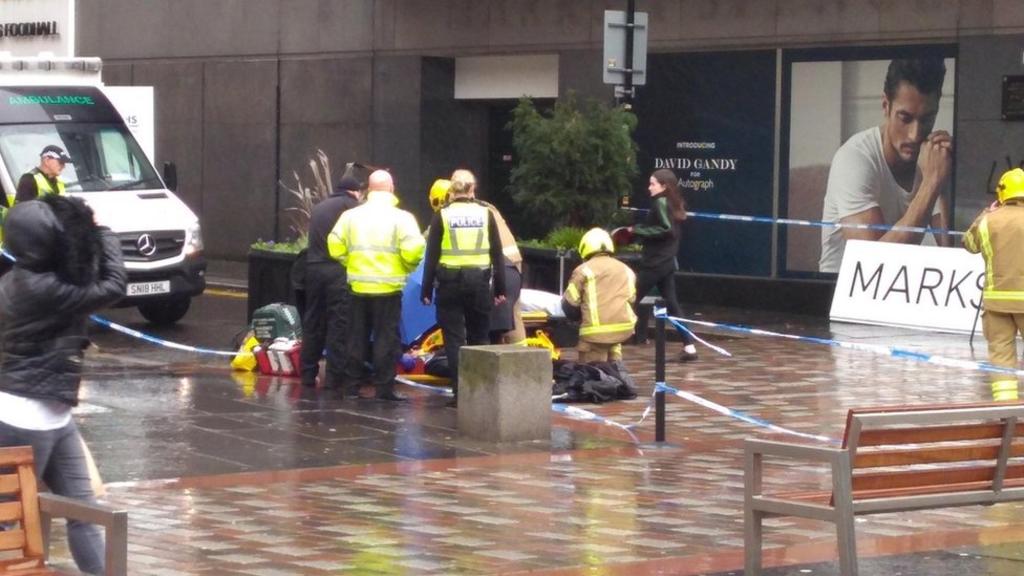

On Friday 21 February 2020, two women were injured in a Glasgow street when a shop sign was dislodged in high winds and landed on them. Were the high winds an act of God or did the store fail to safeguard against this type of incident? Read on …

Two women hit by falling M&S sign in Glasgow city centre

The pedestrians are taken to hospital after the sign landed on them outside the store in Argyle Street.

Related Blog articles dealing with defences to actions in delict:

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/01/26/volenti-non-fit-injuria-or-hell-mend-you/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/12/09/howzat-or-volenti-again/

Copyright Seán J Crossan, 23 December 2019 & 21 February 2020