Photo by Thư Anh on Unsplash

Author’s note: Ms Weddle appealed to the Sheriff Civil Appeal Court where the original decision of the Sheriff (who ruled against her claim) was upheld. The decision was issued on 7 June 2021 and does not contain any surprises.

A link to the Appeal Court’s decision, Danielle Weddle v Glasgow City Council [2021] SAC (Civ) 17 PIC-PN2982-17, can be found below:

https://www.scotcourts.gov.uk/docs/default-source/cos-general-docs/pdf-docs-for-opinions/2021-sac-(civ)-017.pdf?sfvrsn=0

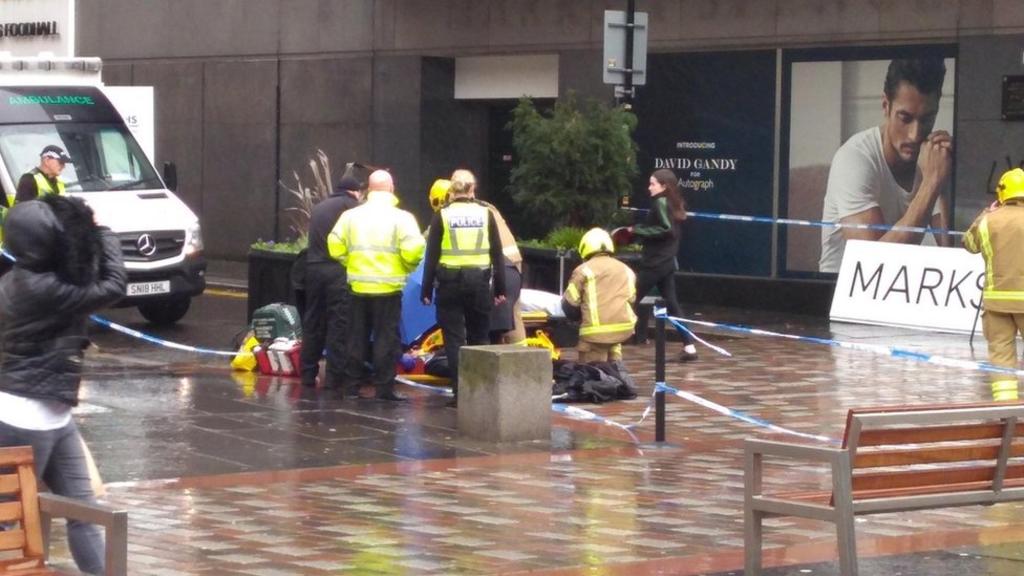

It’s hard to believe that, this month, it will be 5 years since the event infamously dubbed the Glasgow Bin Lorry Crash occurred.

To those readers unfamiliar with the events that happened on 22 December 2014, Harry Clarke, an employee of Glasgow City Council, was responsible for causing the deaths of 6 people and injuring 15 others. Mr Clarke was employed by the City Council as the driver of a bin lorry (garbage truck for our North American readers). He lost control of the vehicle while driving it in Glasgow City Centre. It later emerged that Mr Clarke had a history of illness which caused him to suffer from blackouts. He had not revealed this fact to his employer. Mr Clarke suffered one of those episodes on the day of the accident.

A link to an article which appeared in The Guardian the day after the accident can be found below:

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/dec/23/glasgow-bin-lorry-crash-three-victims-family-named

Clearly, the Council was potentially (vicariously) liable for the actions of its employee to the primary victims in delict (tort), but what about bystanders who witnessed the tragic turn of events and who had no personal or family links with the primary victims (the dead and the injured)?

I’ll discuss this incident later in the Blog in relation to a recent decision of the All Scotland Personal Injury Sheriff Court.

The law of delict and PTSD

Scots law (and indeed the English law) recognises two kinds of victim who can develop psychiatric injuries as a result of the defender’s negligence in these types of situation:

- Primary victims

- Secondary victims

Primary victims are those individuals who have been directly involved in an accident caused by the defender’s negligence. They may have suffered both physical and psychiatric injuries or their injuries may be limited purely to psychiatric damage.

Secondary victims, on the other hand, are not directly involved in the initial accident that occurred as a result of the defender’s negligence. In fact, they may not have witnessed the occurrence of the accident at all.

This category of victim often appears on the scene during the aftermath of the accident as in Bourhill v Young [1943] AC 92 when the important events had already taken place. Alternatively, secondary victims might be related or connected to the primary victims and as such it would be reasonably foreseeable that they would suffer some sort of distress. Whether or not secondary victims can claim compensation for their psychiatric injuries is, however, not always a straightforward matter.

Primary victims have traditionally had a more straightforward task when it comes to convincing the courts that they should be awarded damages for the psychiatric injuries that they have suffered.

As we shall see, strict rules are now in place that will determine whether a secondary victim should succeed in her claim for damages against the defender.

The obstacles facing secondary victims

The ability of secondary victims to bring successful claims for psychiatric injury has been at the heart of some high profile judicial decisions over the last four decades.

In McLoughlin v O’Brian [1983] 1 AC 410, the pursuer’s husband and three children were all victims of a serious car accident which had been caused as a result of the defender’s negligence. One of the pursuer’s daughters was killed in the accident and the surviving family members were all seriously injured. It is important to realise that the pursuer was not physically present at the scene of the accident and she was not informed about the accident until several hours after it had occurred.

When the pursuer reached the hospital she saw for herself the graphic and serious nature of the injuries that her family had suffered. This all proved too much for the pursuer to deal with and she developed a long-running and serious psychiatric condition which she claimed had been caused by the defender’s negligence.

The difficulty for the pursuer was that she was clearly a secondary victim and the law relating to psychiatric injuries was quite clear – only primary victims could be granted compensation for the psychiatric injuries that they had suffered as a result of the defender’s negligence. The House of Lords, therefore, had to consider the issue of whether the pursuer was someone that the defender could reasonably foresee would suffer harm as a result of his negligence. Furthermore, some of the Law Lords felt reasonable foreseeability of harm was not enough and the strength of the pursuer’s relationship with the primary victims had to be examined.

Held: by the House of Lords that the psychiatric injuries suffered by the pursuer were reasonably foreseeable. The ties of love and affection were clearly a crucial feature of her relationship with the primary victims. She was, therefore, entitled to compensation from the defender.

McLoughlin v O’Brian was not without its critics and it did not entirely settle the question of whether secondary victims were entitled to sue for psychiatric injury. Lord Bridge suggested that reasonable foreseeability of the pursuer suffering harm should be enough to establish liability. Lords Wilberforce and Edmund-Davies felt that reasonable foreseeability was only one part of the story. The strength of the pursuer’s relationship with the primary victims was a very important factor in determining whether any claim for psychiatric injury should be allowed.

The decision of Alcock and Others v Chief Constable of the Yorkshire Police [1992] 1 AC 310 that the approach that Lords Wilberforce and Edmund-Davies had taken in McLoughlin was confirmed as correct.

Alcock was regarded as a special case because the pursuers represented a group of individuals who had a broad range of relationships with the primary victims. The pursuers included parents, children, siblings, grandparents, in-laws, fiancés and friends. All these individuals were claiming that they had suffered psychiatric shock as a result of the harm that had been suffered by the primary victims to whom they were connected. The House of Lords was left with the task of deciding which of these secondary victims was entitled to claim compensation for psychiatric injuries.

The facts of Alcock and Others v Chief Constable of the Yorkshire Police [1992] are detailed below:

The events surrounding this case relate to the English FA Cup semi-final which was being contested by Liverpool and Nottingham Forest. The match was being played at the neutral venue of Hillsborough (the Sheffield Wednesday ground) and it was a sellout. The game was also being televised live on the BBC – although individuals who were caught up in the crush could not be identified from the live television pictures. The South Yorkshire Police force which was responsible for policing the match was accused of negligence for the way in which it operated its crowd control procedures. The game had to be stopped after six minutes of play because too many fans had been allowed into a section of the terraces and many of these individuals were crushed against the fencing which prevented access to the pitch.

Ninety-five people died as a result of the incident and at least another 400 had to be treated in hospital for the injuries that they received. The police paid compensation to the primary victims of the incident i.e. those had suffered physical and psychiatric injuries as a result of being directly involved in the accident. This compensation payment, however, did not settle the claims of a group of secondary victims, consisting mainly of relatives of the primary victims. These secondary victims, of course, had not been directly caught up in the incident. Many had, admittedly, been present at Hillsborough and had witnessed the terrible scenes from a distance. Others in the group of secondary victims had witnessed the incident on live television, had been told about the incident by third parties or had gone directly to the ground after hearing the information in order to search for family and friends who were missing presumed injured or dead.

The pursuers attempted to rely upon Lord Bridge’s test in McLoughlin v O’Brian that their psychiatric injuries were reasonably foreseeable and, therefore, they could claim compensation. The House of Lords felt that although the secondary victims had suffered as a result of the incident at Hillsborough, stricter rules had to apply to their claims than was the case with the primary victims. The starting point of any secondary victim’s claim for damages the psychiatric injuries must be reasonably foreseeable. This is only the first hurdle placed in the pursuer’s way. There are a further three tests that pursuers must satisfy:

- Do they belong to a group of individuals that the courts should recognise are capable of suffering psychiatric injury as a result of the defender’s negligence?

- How close to the accident was the pursuer in terms of time and space?

- How was the psychiatric injury caused?

In practice, many pursuers (who are classified as secondary victims) will find the above tests very difficult to satisfy in order to succeed in their claims.

Held: by the House of Lords that all the pursuers failed to meet one of the three tests listed above and, therefore, the claims must fail.

Primary or secondary victim?

What happens, however, when the status of the victim is disputed: in other words, do they fall into the category of a primary or secondary victim?

This was precisely the issue with which the All Scotland Personal Injury Sheriff Court in Edinburgh had to grapple.

The case in question is that of Danielle Weddle v Glasgow City Council [2019] SC EDIN 42. Miss Weddle, a student, witnessed the events of the Bin Lorry Accident. She was present in the City’s George Square as Harry Clarke’s vehicle (the bin lorry) lost control colliding into pedestrians and damaging street furniture. Prior to the incident, Weddle had been standing on the pavement looking at her mobile phone. She looked up when she heard the noise of the collision and saw the damage caused.

When she left George Square shortly afterwards, Weddle came across a dead body (an earlier victim of Harry Clarke’s negligence). She thought that the victim’s intestines were hanging out of the abdomen. Needless to say, she was traumatised by this scene.

She tried to telephone her mother, but was unsuccessful at first. She managed to contact her father and told him she had seen a horrible accident. Mr Weddle then contacted his wife and got her to phone their daughter; which she duly did. Mrs Weddle wanted her daughter to go to hospital. Weddle instead decided to go home by bus. When she got off the bus, she went into a pharmacy in the Cardonald area of Glasgow to seek some help. Mrs Wade, the pharmacist who attended to her, recognised that she was in deep shock. The pharmacist immediately arranged for a GP to come and see Weddle. She was ‘distraught’; given diazepam; and was eventually allowed to go home.

Weddle claimed that as a result of what she had witnessed, she was not able to return to university after the Christmas holidays; she suffered ‘nightmares’ and ‘psychological symptoms such as intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, anxiety and depression’. Her GP subsequently referred her to counselling and she had to take anti-depressants.

To this day, there is no doubt that Weddle has been affected by the events that she witnessed in Glasgow City Centre. She is a victim of post-traumatic stress as a result of what she experienced in Glasgow City Centre on 22 December 2019.

The key question before the All Scotland Personal Injury Sheriff Court was whether Weddle fell into the category of a primary or a secondary victim?

Held: by Sheriff Kenneth J McGowan ‘… that the defender’s employee (Harry Clarke) would not have reasonably foreseen that his driving at the relevant time would have given rise to the risk of physical injury to the pursuer (Weddle); and in any event, that the pursuer did not in fact suffer fear of physical injury to herself at the relevant time; that accordingly, the pursuer does not qualify as a primary victim and she cannot therefore obtain damages for any psychiatric injury suffered by her.‘

A link to Sheriff McGowan’s decision can be found below:

https://www.scotcourts.gov.uk/docs/default-source/cos-general-docs/pdf-docs-for-opinions/2019scedin42.pdf?sfvrsn=0

A link to a report on the BBC website about the outcome of the Weddle case can be found below:

Student refused damages over Glasgow bin lorry crash

The woman suffers from PTSD after witnessing part of the crash which resulted in the death of six people in December 2014.

Copyright Seán J Crossan, 10 December 2019