One of the most important common law duties that an employer has under the contract of employment is to pay wages to the employee.

This duty, of course, is contingent upon the employee carrying out his or her side of the bargain i.e. performing their contractual duties.

The right to be paid fully and on time is a basic right of any employee. Failure by employers to pay wages (wholly or partially) or to delay payment is a serious contractual breach.

Historically, employers could exploit employees by paying them in vouchers or other commodities. Often, these vouchers could be exchanged only in the factory shop. This led Parliament to pass the Truck Acts to prevent such abuses.

Sections 13-27 of the Employment Rights Act 1996 (which replaced the Wages Act 1986) give employees some very important rights as regards the payment of wages.

The National Minimum Wage Act 1998 (and the associated statutory instruments) and the Equality Act 2010 also contain important provisions about wages and other contractual benefits.

There are a number of key issues regarding the payment of wages:

- All employees are entitled to an individual written pay statement (whether a hard or electronic copy)

- The written pay statement must contain certain information

- Pay slips/statements must be given on or before the pay date

- Fixed pay deductions must be shown with detailed amounts and reasons for the deductions e.g. Tax, pensions and national insurance

- Part time workers must get same rate as full time workers (on a pro rata basis)

- Most workers entitled to be paid the National Minimum Wage or the National Minimum Living Wage (if over age 25) (NMW)

- Some workers under age 19 may be entitled to the apprentice rate

Most workers (please note not just employees) are entitled to receive the NMW i.e. over school leaving age. NMW rates are reviewed each year by the Low Pay Commission and changes are usually announced from 1 April each year.

It is a criminal offence not to pay workers the NMW and they can also take (civil) legal action before an Employment Tribunal (or Industrial Tribunal in Northern Ireland) in order to assert this important statutory right.

There are certain individuals who are not entitled to receive the NMW:

- Members of the Armed Forces

- Genuinely self-employed persons

- Prisoners

- Volunteers

- Students doing work placements as part of their studies

- Workers on certain training schemes

- Members of religious communities

- Share fishermen

Pay deductions?

Can be lawful when made by employers …

… but in certain, limited circumstances only.

When exactly are deductions from pay lawful?:

- Required or authorised by legislation (e.g. income tax or national insurance deductions);

- It is authorised by the worker’s contract – provided the worker has been given a written copy of the relevant terms or a written explanation of them before it is made;

- The consent of the worker has been obtained in writing before deduction is made.

Extra protection exists for individuals working in the retail sector making it illegal for employers to deduct more than 10% from the gross amount of any payment of wages (except the final payment on termination of employment).

Employees can take a claim to an Employment Tribunal for unpaid wages or unauthorised deductions from wages. They must do so within 3 months (minus 1 day) from the date that wages should have been paid or, if the deduction is an ongoing one, the time limit runs from the date of the last relevant deduction.

An example of a claim for unpaid wages can be seen below:

Riyad Mahrez and wife ordered to pay former nanny

Equal Pay

Regular readers of the Blog will be aware of the provisions of the Equality Act 2010 in relation to pay and contractual benefits. It will amount to unlawful sex discrimination if an employer pays a female worker less than her male comparator if they are doing:

- Like work

- Work of equal value

- Work rated equivalent

Sick Pay

Some employees may be entitled to receive pay from the employer while absent from work due to ill health e.g. 6 months’ full pay & then 6 months’ half pay. An example of this can be seen below:

Statutory Sick Pay (SSP)

This is relevant in situations where employees are not entitled to receive contractual sick pay. Pre (and probably post Coronavirus crisis) it was payable from the 4th day of sickness absence only. Since the outbreak of the virus, statutory sick pay can paid from the first day of absence for those who either are infected with the virus or are self-isolating.

Contractual sick pay is often much more generous than SSP

2020: £95.85 per week from 6 April (compared to £94.25 SSP in 2019) which is payable for up to 28 weeks.

To be eligible for SSP, the claimant must be an employee earning at least £120 (before tax) per week.

Employees wishing to claim SSP submit a claim in writing (if requested) to their employer who may set a deadline for claims. If the employee doesn’t qualify for SSP, s/he may be eligible for Employment and Support Allowance.

Holiday Pay

As per the Working Time Regulations 1998 (as amended), workers entitled to 5.6 weeks paid holiday entitlement (usually translates into 28 days) per year (Bank and public holidays can be included in this figure).

Some workers do far better in terms of holiday entitlement e.g. teachers and lecturers.

Part-time workers get holiday leave on a pro rata basis: a worker works 3 days a week will have their entitlement calculated by multiplying 3 by 5.6 which comes to 16.8 days of annual paid leave.

Employers usually nominate a date in the year when accrual of holiday pay/entitlement begins e.g. 1 September to 31st August each year. If employees leave during the holiday year, their accrued holiday pay will be part of any final payment they receive.

Holiday entitlement means that workers have the right to:

- get paid for leave that they build up (‘accrue’) in respect of holiday entitlement during maternity, paternity and adoption leave

- build up holiday entitlement while off work sick

- choose to take holiday(s) instead of sick leave.

Guarantee payments

Lay-offs & short-time working

Employers can ask you to stay at home or take unpaid leave (lay-offs/short time working) if there’s not enough work for you as an alternative to making redundancies. There should be a clause in the contract of employment addressing such a contingency.

Employees are entitled to guarantee pay during lay-off or short-time working. The maximum which can be paid is £30 a day for 5 days in any 3-month period – so a maximum of £150 can be paid to the employee in question.

If the employee usually earn less than £30 a day, s/he will get their normal daily rate. Part-time employees will be paid on a pro rata basis.

How long can employees be laid-off/placed on short-time working?

There’s no limit for how long employees can be laid-off or put on short-time. They could apply for redundancy and claim redundancy pay if the lay-off/short-term working period has been:

- 4 weeks in a row

- 6 weeks in a 13-week period

Eligibility for statutory lay-off pay

To be eligible, employees must:

- have been employed continuously for 1 month (includes part-time workers)

- reasonably make sure you’re available for work

- not refuse any reasonable alternative work (including work not in the contract)

- Not have been laid-off because of industrial action

- Employer may have their own guarantee pay scheme

- It can’t be less than the statutory arrangements.

- If you get employer’s payments, you don’t get statutory pay in addition to this

- Failure to receive guarantee payments can give rise to Employment Tribunal claims.

This is an extremely relevant issue with Coronavirus, but many employers are choosing to take advantage of the UK Government’s Furlough Scheme whereby the State meets 80% of the cost of an employee’s wages because the business is prevented from trading.

Redundancy payments

If an employee is being made redundant, s/he may be entitled to receive a statutory redundancy payment. To be eligible for such a payment, employees must have been employed continuously for more than 2 years.

The current weekly pay used to calculate redundancy payments is £525.

Employees will receive:

- half a week’s pay for each full year that they were employed under 22 years old

- one week’s pay for each full year they were employed between 22 and 40 years old

- one and half week’s pay for each full year they were employed from age 41 or older

Redundancy payments are capped at £525 a week (£508 if you were made redundant before 6 April 2019).

Please find below a link which helps employees facing redundancy to calculate their redundancy payment:

https://www.gov.uk/calculate-your-redundancy-pay

Family friendly payments

Employers also have to be mindful of the following issues:

- Paternity pay

- Maternity Pay

- Shared Parental Pay

- Maternity Allowance

- Adoption Pay

- Bereavement Pay

Employers can easily keep up to date with the statutory rates for family friendly payments by using the link below on the UK Government’s website:

https://www.gov.uk/maternity-paternity-calculator

What happens if the employer becomes insolvent and goes into liquidation?

Ultimately, the State will pay employees their wages, redundancy pay, holiday pay and unpaid commission that they would have been owed. This why the UK Government maintains a social security fund supported by national insurance contributions.

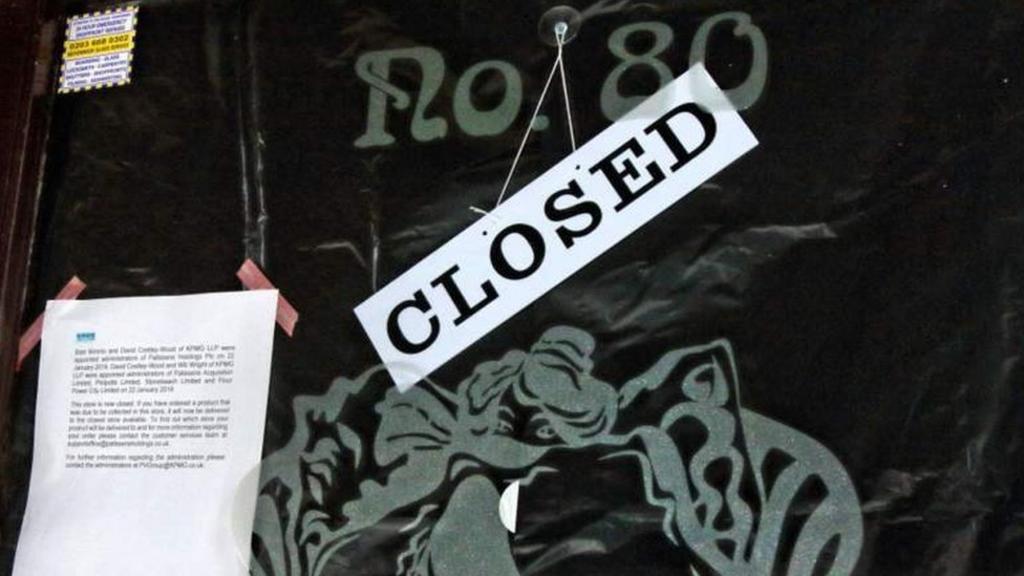

An example of a UK business forced into liquidation can be seen below:

Patisserie Valerie: Redundant staff ‘not receiving final pay’

Up to 900 workers lost their jobs when administrators closed 70 of the cafe chain’s outlets. Disclaimer:

Conclusion

Payment of wages is one of the most important duties that an employer must fulfil. It is also an area which is highly regulated by law, for example:

- The common law

- The Employment Rights Act 1996

- The Working Time Regulations 1998

- The National Minimum Wage Act 1998

- The Equality Act 2010

- Family friendly legislation e.g. adoption, bereavement, maternity, paternity

Failure by an employer to pay an employee (and workers) their wages and other entitlements can lead to the possibility of claims being submitted to an Employment Tribunal. The basic advice to employers is make sure you stay on top of this important area of employment law because it changes on a regular basis and ignorance of the law is no excuse.

Related Blog Articles:

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2020/01/30/2020-same-old-sexism-yes-equal-pay-again/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2020/01/10/new-year-same-old-story/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/05/13/inequality-in-the-uk/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/03/31/the-gender-pay-gap/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/04/05/the-gender-pay-gap-part-2/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/06/26/ouch/

https://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/06/20/sexism-in-the-uk/

Thttps://seancrossansscotslaw.com/2019/04/30/paternity-leave/

Copyright Seán J Crossan, 5 April 2020